Introduction

By Jose Ruiz | Alder Koten Institute | Gonzaga University

Chick-fil-A is a chain restaurant and headquartered in the Atlanta suburb of College Park, Georgia. Chick-fil-A was founded in 1946 and steadily grew into the second largest quick-service chicken restaurant chain in the United States. Strongly influenced by the founder’s Southern Baptist beliefs, Chick-fil-A has generated controversy from outspoken Christian values. Unlike most fast food restaurants and retail chain stores, Chick-fil-A restaurants are closed for business on Sunday to observe a day of rest. Old-school values and strong adherence to the founder’s Southern Baptist roots has been the subject of public controversy, but Chick-fil-A’s customer service is exemplary.

A few years ago, my family and I stopped for lunch at our local Chick-fil-A restaurant. During lunch, my son asked, “Have you noticed how people here at Chick-fil-A are always in a good mood and willing to help? Just like in the Apple store. At McDonald’s everyone always seems mad.” My son then asked the question that has prompted most of the research I have done.

“Dad, do you know why some places make people happy and why other places make people mad?”

After pondering the question, my initial thoughts drifted around the concepts of training, processes, and procedures. This was too complicated to explain to a 9 year-old, but dad has all the answers. I kept it as simple as I could: “This is all about training people on how procedures should be done” Challenging my answer, my son asked, “So, Wal-Mart doesn’t train people? McDonald’s doesn’t tell people what to do? Do people get mad because they aren’t told what to do?” My son’s questions prompted me to reflect.

To believe that McDonald’s lacks process documentation or training for their employees is unimaginable. Founders Richard and Maurice McDonald designed the company’s service model using production line principles. The introduction of the “Speedee Service System” in 1948 furthered the principles of the modern fast-food restaurant. McDonalds is the poster child of process, procedures, and training. My son’s comments and his questions stuck in my mind, like a song a person hums obsessively to remember the name. After a few hours, the answer hit me. The answer is culture! This realization came with an incredible amount of questions.

In 2006, Mark Fields, at the time, the President of Ford Motor Company, hung Peter Drucker’s quote “Culture Eats Strategy For Breakfast” in the war room. Also hanging on the wall is “Culture is unspoken, but powerful. It develops over time — difficult to change” 1.

Both are a reflection of Field’s awareness that any strategy or business model needs to be supported by the culture in order to be successful.

At Alder Koten we worked on an assignment during the summer of 2013 and concluded that our client’s culture was a barrier to effectively implement the desired talent strategy. Our client quickly agreed and proceeded to ask us if we could clarify what it was and what part of the culture needed to change. We could not. At least not in the same way we could assess individuals with competency models or psychometric assessments.

There are tools such as the Denison Culture Model 2, but the tool is a benchmark against what Denison describes as effective organizations. The definition of ‘effective organization’ is defined by Denison within the context of Standard and Poor’s financial ratios as indicators of performance. The definition is debatable and Denison’s focus on finding a correlation between corporate culture and the bottom line is a barrier if dealing with organizations that define their effectiveness beyond profits and return on investment.

Culture can be compared to the words love, leadership, and values. Many people have tried to define the word culture, resulting in varying definitions. Culture is an invisible, constantly changing force. Most leaders, and managers have a implicit idea of what culture is, and they know that culture is a critical part of any institution, society, or organization, but they have a hard time defining culture, explaining culture, and most importantly quantifying culture. In the article “Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast: Wait…Can’t The Two Align?” Torben states, “Culture means different things to different people. It is emotional, ever-changing, and complex. Culture is human, vulnerable, and as moody as the people who define it”3. A first step towards measuring culture is clearly defining culture and its elements.

This paper will provide a definition of organizational culture and present a framework to serve as a foundation for measuring organizational culture. The Framework takes into consideration the influence of other cultural environments such as family and society. It can be used as a tool for future research and the development, helping to evaluate and quantify an organization’s culture.

Defining Culture

In his Harvard Business Review article What is Organizational Culture? And Why Should we Care? Watkins declares: “while there is universal agreement that it exists, and that it plays a crucial role in shaping behavior in organizations, there is little consensus on what organizational culture actually is.” Watkins continues by saying that: “without a reasonable definition (or definitions) of culture, we cannot hope to understand its connections to other key elements of the organization, such as structure and incentive systems. Nor can we develop good approaches to analyzing, preserving and transforming cultures.”4 Most commonly accepted definitions of organizational culture imply social and psychological elements that are shared by a group. Many include behaviors, habits, practices, drivers, beliefs, and values.

External influences and societal culture are important elements when studying and analyzing organizational culture. In the preface of Strategic Organizational Communication in a Global Economy, Conrad and Poole state that “Organizations are embedded in societies and cannot be understood outside of a society’s beliefs, values, structures, practices, tension and ways of managing those tensions“5. Organizational culture cannot be decoupled from societal culture.

Geert Hofstede is a Dutch social psychologist and former IBM employee and well known for his pioneering research on cross-cultural groups and organizations. He defines culture as “the code, the core logic, the software of the mind that organizes the behavior of the people.” Hofstede developed a framework that describes the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis. Hofstede developed a framework that describes the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis.

Several fields use the theory as a paradigm for research, particularly in cross-cultural psychology, international management, and cross-cultural communication.

The definition of organizational culture has to build upon the definition of culture. “Culture consists of the unwritten rules of the social game. It is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group of category of people from others”6. A group of people can be defined as a family, a neighborhood, a church, a society, a nation, or an organization. Organizational culture is a culture characterized by the members of the organization within the context of a broader culture.

“Organizations are embedded in societies and cannot be understood outside of a society’s beliefs, values, structures, practices, tension and ways of managing those tensions“

The Cultural Profile And The Cultural Environment

The term “cultural model,” drawn from cognitive anthropology, indicates an organized set of ideas that are shared by members of a cultural group

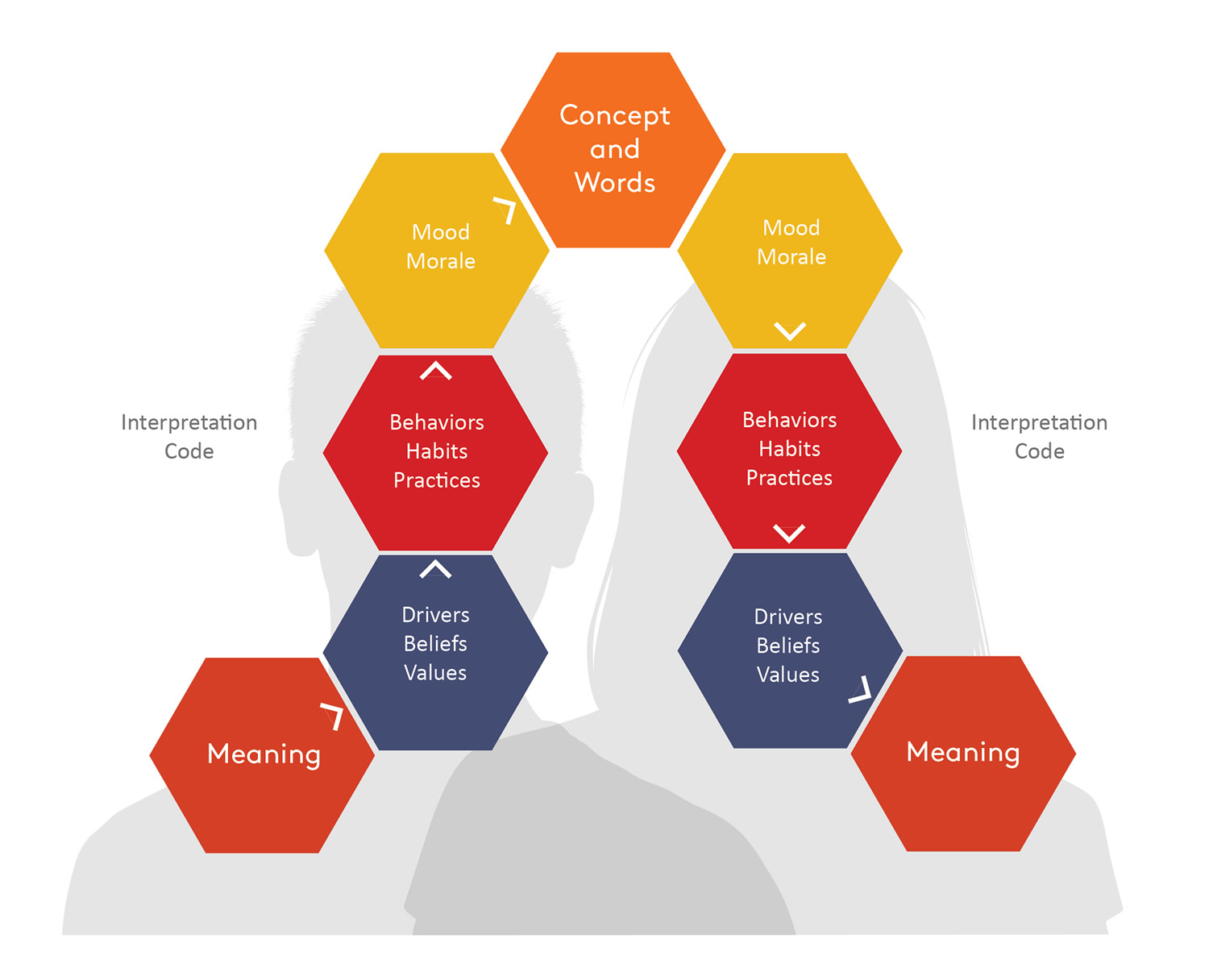

There are two components in this paper’s definition of culture:

The Cultural Profile: Culture as the collection of deeply ingrained values and beliefs that drive our individual behaviors.

The Cultural Environment: Culture as the shared beliefs and values of a group.

The cultural profile is defined by the deeply ingrained values and beliefs that are learned from a cultural environment. This includes personal experiences, societal culture, family culture, and many others including corporate culture. The cultural profile, along with the cultural profile of others creates a cultural environment that continuously reshapes our cultural profile as we continuously reshape our cultural environment.

Family, schools, a group of friends, neighborhoods, churches, society, nations, and organizations are all cultural environments.

The family’s cultural environment begins to shape the cultural profile of a person when they are babies. It is further developed by societal culture as the individual grows and interacts with a broader group of people. A person is influenced by the interaction, and they influence others through that interaction.

A person influences their cultural environments, and they are influenced by their cultural environments.

It was around 11PM on a late May evening when my wife told me it was time. Our first-born was ready to arrive into our lives. A few hours later our son was born healthy, happy and oblivious. In his book, A Hidden Wholeness, Parker Palmer reminds us “we arrive in this world undivided, integral, and whole”7. Our son was quickly checked, cleaned, and placed in my arms unaffected by anything from our world, but then it began. He was born, just like the rest of us, without any predefined values, beliefs, patterns or established behaviors. He was born without a cultural profile. Only minutes after he was born a series of transactional activities began to shape his basic behaviors such as the time he was to eat and sleep. If you are a parent you know this: after babies are born our first job is to keep them healthy and safe; the second is to train them to sleep through the night. Unfortunately for sleep-deprived parents this does not happen overnight. Parents gradually train children to adapt to expectations and their cultural profile is shaped over a period of many years. Winston Churchill said: “we shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” To paraphrase Churchill: We shape our cultures, and afterwards our cultures shape us. However, an institution shapes us all long before we are capable of contributing to the shaping of another institution, organization, or culture. We arrive in this world unexposed in every sense and placed in the arms of our parents and into the institution of family: the basic unit of society. Family is where our cultural profile begins to take shape and where our journey begins.

In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Work Davies defines parenting as the process of promoting and supporting the physical, emotional, social, and intellectual development of a child from infancy to adulthood. Parenting refers to the aspects of raising a child aside from the biological relationship8.

All of us are born with basic behaviors and survival instincts. However, our habits, attitudes, sense of purpose, beliefs, and values are learned and shaped. We don’t inherent them biologically, but we do inherit many of them psychologically.

Many thoughts went through our minds and many doubts surfaced when my wife first told me we were going to be parents. Many of those thoughts were questions about our preparation and our parenting capabilities. She began to acquire a library of books on different parenting topics and read like never before during the pregnancy. We worked hard to eliminate our feeling of unpreparedness, but as all parents know: that’s a difficult thing to achieve. There is no doubt in my mind that we learned a great deal and our parenting style was influenced by what we learned, however our efforts during that nine month period represent only a very small part of the elements that shaped our family institution and influenced our children. The biggest influence exerted upon our children comes from our collective cultural profiles and the cultural environments that influenced them. All the things we learned years before our children were born and were combined into our family’s cultural environment.

Sara Harkness is a professor of human development at the University of Connecticut and she has spent decades compiling and analyzing the impact of cultures in parenting. She defines the concept of parental cultural environment as parental ethnotheories: “cultural models that parents hold regarding children, families, and themselves as parents”9. The term “cultural model,” drawn from cognitive anthropology, indicates an organized set of ideas that are shared by members of a cultural group10. These represent what we intuitively believe is the right way to raise a child. The word intuitively is important because “these are the choices we make without realizing that we’re making choices”11. This concept is key in isolating the definition of culture and organizational culture.

Isolating The Definition Of Organizational Culture

The incorporation of behaviors, habits, and practices into some definitions of organizational culture has led to mechanisms that attempt to quantify organizational culture through perception and organizational climate surveys that lead to the measurement of the manifestations (organizational climate) and reasons (behaviors, habits, and practices), but not the cause (drivers, beliefs, and values.)

As stated by Day, culture is intuitive and it drives the choices that individuals make without realizing that they’re making choices.

This concept can allow us to isolate organizational culture to include the elements that intuitively and sometimes unconsciously determine our choices: drivers, beliefs, and values while redefining behaviors, habits, and practices as the organizational identity.

The combination of organizational culture, the organizational identity, and external forces produce the organizational climate.

Measuring Organizational Culture

Surveys are a common method for measuring organizational culture. These can be effective in measuring climate and identity, but they can present challenges when attempting to measure values, beliefs, and drivers. One challenge is described by Hofstede as the complexity of distinguishing between desirable and the desired: “how people think the world ought to be versus what people want for themselves” 12. When asked about their values people tend to respond in alignment with what they consider morally correct (desirable) in their cultural environment while their behavior adheres to their less virtuous desires.

Another challenge is that words can have different meanings based on an individual’s interpretation. Ethical and cultural relativism comes into play. Ethical relativism is defined by Wall as “the claim that there is no correct set of moral obligations and values” 13. Cultural relativism is a doctrine originating in American cultural anthropology14. The broad principle of cultural relativism is that judgments and interpretations are based on the individual’s culture15 .

Every individual has an interpretation code based on his or her cultural profile. The real meaning of a person’s response to a question is dependent on how their interpretation code understands the questions, and how the interviewer’s interpretation code understands the answer.

For example, a survey can be applied in an organization, and it can determine that ‘integrity’ is a core value in the organization’s culture. Integrity can mean different things to different individuals based on their interpretation code.

Let’s consider the following situation: A manager and a subordinate travel to New York City to attend a symposium. Both get in a car after the opening dinner and head to the hotel. It is a freezing night, and the manager is driving. When the first traffic light on the road turns red the manager breaks, but the car slides on black ice and hits a light post. Nobody gets hurt, but there is slight damage to the car. The driver has the obligation to report the incident to the police, the rental car company, and the insurance carrier. At that moment, the manager turns to his subordinate and says: “I had two glasses of wine at the dinner. It is most likely not an issue, but can you take the wheel and say you were driving when the police arrive?” The subordinate agrees that it is the best thing to do and takes the wheel.

Does it reflect a lack of integrity on the part of the manager?

Does it reflect a lack of integrity on the part of the subordinate?

Does it reflect a lack of integrity in the organization’s culture?

The answers will depend on the interpretation code of whoever is being asked. Most people will reply that it does reflect a lack of integrity in Countries such as Germany and the United States, where societal culture places a strong value on the adherence to rules and norms. The answers will be different in countries such as Mexico and Italy where practical circumstances take precedence over rules and standards. In particular societal cultures, such as Korea, it would be a lack of integrity on the part of the subordinate to not protect his superior (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2010).

A model used to measure organizational culture must consider the relative nature of cultures. “People born and raised in different times, different cultures, and different parts of the world have different moral beliefs. None of these is any better than any other” (Wall, 2008, p.18). In order to be effective in measuring organizational culture, cultural relativism must be applied and the dynamics of relative ethics must the taken into consideration. During assessment questions and responses should be made and understood in terms of an individual’s interpretation code; not the interviewer’s.

Changing Values And Beliefs

If we accept that values are deeply ingrained beliefs that drive our decisions and behaviors at the instinct and subconscious level; we must also accept that we cannot easily change another person’s values. The purpose of measuring an organization’s culture is to understand the underlying values of the individuals in the organization, manage how those values manifest in beliefs and coexist, and shape attitudes that can foster constructive conflict. Conflict as a product of multiple cultural profiles coming together in a cultural environment is inevitable and natural. It takes groups down the path of questioning given assumptions and in the process forces them to think different. Learning how other cultures (family, societal, national, organizational, or any other type) perceive the world helps develop an intercultural mindset (16). The intercultural mindset enables judgments from multiple frames of reference leading to empathetically engaging with the viewpoints of other cultural profiles (Evanoff, 2006).

The above statement does not imply that we can harmonize all differences. Measuring cultural profiles and cultural environments can help us identify when and where harmonizing is possible and also when it is simply best to foster a safe distance. It can also support adaptation, integration. Adaptation is the process by which an individual can adapt their cultural profile to the norms of a cultural environment without changing their beliefs or values (Evanoff, 2006). Integration is the process by which an individual incorporates beliefs and values from the cultural environment into their cultural profile (Evanoff, 2006). Transformation is an internal, fundamental, and permanent shift in our beliefs.

Ten Organizational Culture Dimensions

If we apply ethical and cultural relativism, the methods used to evaluate and measure organizational culture cannot be based on a benchmark that attempts to quantify right or wrong, good or bad.

The following model builds on Hofstede’s approach identifying and applying a dimension with two possible extremes.

The model presents ten belief driven dimensions that can have a significant impact on how individuals interact as a group with shared goals and responsibilities. The model does not seek to establish a correct or incorrect pattern for a group. It is meant to help visualize the belief pattern of a cultural profile and a cultural environment to support transformation, integration, and adaptation.

Section

Discipline

The discipline dimension measures the individual’s beliefs regarding discipline and how it reflects on their structure, predictability, work ethic, habits and behaviors.

Flexible

The left extreme (flexible) characterizes individuals that believe the ability to be reactive and highly capable of improvisation is important. They accept high unpredictability as a consequence. Individuals in these groups tend to be flexible about processes, procedures, and time integrating social and emotional circumstances into the variables that affect the outcome and predictability of a task. These groups treat tasks as non-sequential and place a high value on flexible habits and their capability to react to unpredictable circumstances in a creative fashion. They often see schedules, plans, and commitments as flexible and dependent on external circumstances.

Strict

The right extreme (strict) characterizes individuals that believe that small persistent tasks and actions lead to results and greater goals. These individuals are willing to sacrifice their immediate comfort in order to persist and achieve predictable results with a strong focus on processes and procedures. Individuals detach social and emotional circumstances from the task at hand. These groups place a high value on punctuality and treat tasks as sequential, placing a value on planning, meticulously executing the plan, and staying on schedule. They feel that potential deviations that can be a product of external circumstances should be predicted, planned and managed in a proactive manner.

Formality

The formality dimension measures the individual’s beliefs on how instructions, laws, rules, values, and obligations should be perceived and treated within the group.

Ambiguous

The left extreme (Ambiguous) characterizes individuals that believe that circumstances and relationships should dictate specific outcomes. Their response to a specific situation may change based on the exceptional nature of circumstances including what is happening in the moment, and who’s involved. Individuals in this type of culture tend to feel comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity because they know things become clear once they are placed into the context of a unique set of circumstances.

Defined

The right extreme (Defined) characterizes individuals that believe in strict adherence to laws, rules, values, and obligations. Individuals in this type of culture tend to imply equality in the sense that all persons, employees, or citizens, considered under the rule should be treated the same regardless of circumstance. People in these environments maintain rigid codes of belief and are intolerant to open interpretation of rules. They tend to feel very uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity.

Awareness

The awareness dimension measures the individual’s beliefs about whether the focus of the individual or the organization should be internal or external.

Internal

The left extreme (internal) characterizes individuals that believe that survival and progress are based on internal awareness and the capability to adapt to a changing environment. Individuals in this type of culture believe that the strength, bond, effectiveness, and efficiency of the group allows them to better deal with external pressures and changes that are beyond their control. Their focus is on adapting.

External

The right extreme (external) characterizes individuals that believe that survival and progress is based on external awareness and driving change in their environment. People in these environments believe that they need to drive change to minimize potential issues that could be beyond their control in order to better position themselves to be effective and efficient. Their focus is on driving change.

Fertility

The fertility dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to the support of growth, change, and development of people, ideas and concepts.

Open

The left extreme (open) characterizes individuals that believe it is important to be accessible and open to new people, ideas, and concepts. These type of individuals are willing to take measured risks and explore new things. They tend to adapt, and their styles tend to change based on the challenge at hand and the strength and weaknesses of other members of the group. Individuals in these groups tend to balance between adapting themselves to the environment and forcing a change in the environment in order to create a new set of circumstances. They favor diversity and take great pride in being innovators and pioneers. Their awareness tends to center on external circumstances and factors that they need to consider to challenge the status quo.

Closed

The right extreme (closed) characterizes individuals that believe it is important to be protective of their environment, legacy, and heritage. Individuals in these groups tend to have a very clear role and purpose within the organization with clearly defined and strict codes of principles and behaviors. These groups tend to place a high value on homogeneity, stability, and certainty avoiding actions that can put them at risk. They are cautious when it comes to ideas, concepts, and outsiders that can alter the stability and certainty of the group. These groups tend to focus on gradually adapting themselves to the environment and take great pride in their resilience, predictability, and uniqueness. Their awareness tends to center on internal circumstances and factors that may affect the status quo.

Status

The status dimension measures how individuals perceive and react to their relative, social, and professional standing.

Attribution

The left extreme (attribution) characterizes individuals that believe others should attribute a particular status to individuals based on whom they are. Power, title, lineage, and position matter to these persons, and should be factors that influence the standing of people within the organization. Individuals in these groups seek respect and influence based on whom they know and place a high value on authority, especially when decisions have to be made, and favors can be exchanged. These groups see respect and loyalty for superiors as a measure of an individual’s commitment to the organization and a right of passage in order to move up in the hierarchy.

Accomplishment

The right extreme (accomplishment) characterizes individuals that believe status should be based on achievement and performance regardless of whom they are or where they come from. Age, race, gender, or lineage are not factors that define the status. These individuals value systems in which people are evaluated based on their capabilities and move ahead on the basis of achievement and merit. In these environments, titles are used for practical reasons, and when they are relevant to accomplishing specific tasks or defining responsibilities. They value organizations where knowledge, experience, and how effective a person is in performing their role define hierarchies and respect.

Authority

The authority dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to how groups define power, make decisions, manage control, and enforce discipline.

Autocratic

The left extreme (autocratic) characterizes individuals that believe decision-making should concentrated in the top ranks of a hierarchical organization. These individuals tend to favor making decisions within a controlled group that also decides who will deliver. People with authority in these groups feel that it is their duty to dictate what needs to be done so the group can function effectively. They focus on assigning and managing tasks while retaining responsibilities. These individuals place a high value on the chain of command and strict lines of authority. They rely on them in order to distribute work, monitor progress and achieve results.

Participative

The right extreme (participative) characterizes individuals that believe decision-making should be spread across different levels of the organization and involve a participative process. These individuals tend to place a high value on their ability to collaborate and achieve consensus across diverse teams. Individuals with authority in these groups feel that it is not their responsibility to make decisions but rather lead teams to make them. These individuals believe in hierarchies that tend to be flat with top-light teams of leaders focused on assigning responsibility.

Purpose

The purpose dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to the

elements that should drive behavior and the reason for which individuals do things within the context of a narrow, short-term goal or a broad, long-term focus.

Organic

The left extreme (organic) characterizes individuals that believe that it is crucial to consider the impact of today’s actions on tomorrow. Developing the means, processes, and capabilities take precedence over short-term goals to guarantee sustainable long-term progress. In other words, the ends do not justify the means. These individuals see results as the consequence of a healthy organization and not specifically the purpose of the organization. These Individuals value long term effectiveness and efficiency and are willing to sacrifice results today in order to achieve sustainable results tomorrow.

Mechanic

The right extreme (mechanic) characterizes individuals that believe that the purpose of the organization is to achieve specific goals, and a strong focus is placed on the short-term effectiveness of the organization. For these individuals, the end justifies the means. They can adapt, tolerate, and accept different methods in order to achieve the result. These Individuals value short-term effectiveness and efficiency and will work to extract as much as possible today, assuming that tomorrow will bring a different set of unknown circumstances to which the will find a way to adapt.

Reliance

The reliance dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to the level of independence of people in the group from the rest of the organization or their external environment in order to achieve their goals and tasks.

Dependent

The left extreme (dependent) characterizes individuals that believe their ability to achieve their goals and objectives are dependent on external forces that are beyond their realm of control. These individuals feel that they continuously have to work around obstacles in their environment in order to achieve results. They place a high value on the support they may or may not get from others in order to be successful. These individuals tend to attribute their success or failure to their ability to obtain external support and tend to deflect responsibility onto factors that are controlled by someone else.

Independent

The right extreme (independent) characterizes individuals that believe they must manage or control everything that affects their ability to achieve their goals and objectives. This includes working with other people within their group and managing the complexities of their environment. These individuals believe that it is their responsibility to navigate obstacles and drive expected results regardless of the external forces that can work against them.

Community

The community dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to how the needs and purpose of a person are balanced against the needs and purpose of the group.

Group

The left extreme (group) characterizes individuals that think of themselves as part of a group and believe that the group that provides a larger, stable, and dependable structure is more important than themselves. They consider the group first since it provides help and safety, in exchange for loyalty. These individuals feel a strong sense of empathy to others and acknowledge interdependence. They understand the benefits and are willing to maintain this interdependence by doing for others what they expect others to do for them. The group always comes before the individual, but it is important to note that the group is not the broad organization. It can be a close-knit group of people that watch over each other within a larger organization.

Individual

The right extreme (individual) characterizes individuals that believe in personal freedom and achievement and place themselves before the group. They feel it is more important to focus on individual goals and desires and value independence and self-reliance so that they can contribute to the community as and if they wish. These individuals see the organization as an enabler and their relationship with the community exists for mutual benefit and synergy. They believe that individuals must make their decisions and that they must take care of themselves in order for the broader group to be healthy and prevail.

Involvement

The involvement dimension measures the individual’s beliefs related to blending their personal, social and work life.

Diffuse

The left extreme (diffuse) characterizes individuals that believe an overlap between their work, social, and personal life is natural and acceptable. These individuals believe that the context of work or personal lives should not limit or confine good relationships. They feel personal relationships are vital to achieving business objectives. Their relationships with others are treated the same, whether they are at work or meeting socially. These individuals feel that spending time outside work hours with colleagues and clients is important to build trust and cohesive teams.

Specific

The right extreme (specific) characterizes individuals that believe it is healthy and natural to keep work, social, and personal lives separate. These individuals believe that social relationships do not have much of an impact on work objectives. While they can understand that good relationships are important, they feel that people can work together without necessarily having a strong social relationship outside of work. In many instances, these individuals tend to believe that bringing personal and social relationships into the workplace can be both distracting and detrimental to fact-based decisions.

Assessing The Ten Organizational Culture Dimensions

Assessing The Ten Organizational Culture DimensionsA method to evaluate the ten organizational culture dimensions is an assessment that evaluates and grades an individual on each of the ten organizational culture dimensions. Each dimension is graded on a scale from -10 to +10. The array of grades for the ten dimensions represents the individual’s culture profile.

The grades of all of the individuals in a cultural environment or group are used to obtain a statistical profile for a particular organizational culture dimension. The resulting statistical profiles for all cultural dimensions constitute the profile for the cultural environment.

The statistical aggregate of the ten dimensions can help identify essential characteristics of an organization and the organization’s tolerance for individuals that fit or do not fit into the group’s beliefs. For example, a tall and narrow statistical distribution curve for a dimension signals little diversity and tolerance for variation of beliefs in the group for that particular dimension. In contrast, a flat wide statistical distribution curve would indicate high diversity and tolerance in the beliefs related to the dimension.

Conclusion

This paper provided a definition of organizational culture and presented a framework to serve as a foundation for measuring organizational culture. The Framework takes into consideration the influence of other cultural environments such as family and society and can be used as a tool for future research and the development, helping to evaluate and quantify an organization’s culture.

Organizational culture plays a crucial role in shaping organizations and cannot be decoupled from societal culture. The definition of organizational culture presented in this paper builds on the broad definition of culture and narrows the scope to only include values, beliefs, and drivers, isolating behaviors, habits, and practices under the concept of organizational identity.

Individual beliefs need to be assessed to evaluate the culture of a group given that culture is defined as the shared values, beliefs, and drivers of a group. The cultural profile is the deeply ingrained values and beliefs that are learned from a cultural environment. The cultural profile, along with the cultural profile of others creates a cultural environment that continuously reshapes our cultural profile as we continuously reshape our cultural environment. Family, schools, a group of friends, neighborhoods, churches, society, nations, and organizations are all cultural environments. Organizational culture is the cultural environment of an organization.

In order to be effective in measuring organizational culture, cultural relativism must be applied, and the dynamics of relative ethics must the taken into consideration. During assessments, questions and responses should be made and understood in terms of an individual’s interpretation code.

The ten organizational culture dimensions provide a framework for measuring the organization’s cultural environment through the cultural profiles of those who comprise this. The method for measuring the ten dimensions focuses on individual beliefs that drive practices and behaviors.

References

McCracken, J. (2006, January 23). ‘Way Forward’ Requires Culture Shift at Ford. The Wall Street Journal.

Chick-Fil-A “Company Fact Sheet”. Retrieved July 30, 2012. “Headquarters Chick-fil-A, Inc. 5200 Buffington Road Atlanta, GA 30349-2998”

Conrad, C., & Poole, M. (2012). Strategic organizational communication: In a global economy (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadworth.

D’Andrade, R., & Strauss, C. (Eds.) (1992). Human motives and cultural models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, M., & Barton, R. (2000). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Work. New York City: Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated.

Day, N. (2013, April 10). No Big Deal, but This Researcher’s Theory Explains Everything About How Americans Parent. Slate.

Denison, D. (1984). Bringing corporate culture to the bottom line.Organizational Dynamics, 5-22.

Evanoff, R. (2006). “Integration in Intercultural Ethics.” Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20, 241-437. Retrieved from: Intercultural Communication: A Gonzaga Edition Reader.

Harkness, S., & Super, C. (2006). Themes and Variations: Parental Ethnotheories in Western Cultures.

Hofstede, Geert (2001). Culture’s Consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G.J., (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software for the Mind (3rd ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Jarvie, I.C. 1975. Cultural relativism again. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 5:343-53.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1972. Cultural Relativism. New York: Random House.

Quinn, N., & Holland, D. (1987). Culture and cognition. In D. Holland & N. Quinn (Eds.), Cultural models in language and thought (pp. 3_42). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ruiz, J (2013) Alder Koten Organizational Culture DNA Model. The Alder Koten Institute.

Tennekes, J. 1971. Anthropology, Relativism and Method. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Torben, R. (2013, August 1). Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast: Wait…Can’t The Two Align? Leadership Mag.

Wall, T.F. (2008). Thinking critically about moral problems. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Watkins, M. (2013, May 15). What is Organizational Culture? And Why Should we Care? Harvard Business Review.